How Amsterdam became a bike city

In 2025, Amsterdam will be 750 years old! Good reason for us at Amsterdam Bike City to delve into the history of the cycling city. The first bicycles appeared Some 600 years after Amsterdam was founded. They never disappeared, although in the 1960s they were in danger of being pushed off the road. After a tough battle against the space-claiming car, Amsterdam started taking the bicycle seriously and the city grew into one of the best cycling cities in the world.

Bicycles that you see everywhere now in Amsterdam are actually a quite young phenomenon. Until the end of the 19th century, pedestrians were king of the road. Walking was the most common means of transport in the city. And also, of course, carts, horse-drawn carriages and from the 17th century noisy horse-drawn carriages and trams. But no bicycles, let alone cars.

The first cyclists in Amsterdam

From the end of the 19th century, the streetscape changed: the first ‘carriages with combustion engines’ (cars) appeared, as did the first cyclists. ‘Vélocipèdes started to become fashionable in Amsterdam’, wrote the newspaper Arnhemse Courant in 1868: ‘Sometimes one sees three or four of them patrolling Leidschestraat at the same time’. The bicycle, especially the ‘Hoge Bi’* that flourished between 1871 and 1880, was something for young, sporty, wealthy men. Cycling clubs were founded, indoor riding schools were set up to teach cycling, and the new vehicles were seen a lot, especially in the Vondelpark and the Plantage.

* ‘Hoge Bi’, in English ‘penny-farthing’, is the historic bicycle with a large wheel in the front and a small one in the back.

Cyclists in Amsterdam’s Vondelpark, around 1910. Photo: Amsterdam City Archives

‘Everyone is cycling here’

At first, bicycles were expensive and exclusive. But that changed. From 1918 onwards, bicycles quickly became cheaper. ‘Everyone cycles. Eight years old or eighty, mayor, bridge keeper, nose-picker or doctor: everything cycles here’, German writer Konrad Merz writes around 1920 about Amsterdam. The birth of the bicycle city Amsterdam took place in the 1920s. Bicycling spontaneously became the means of transport for the city, without much government guidance. In 1930, a third of traffic consisted of cyclists, pedestrians were another third, and public transport a quarter. Only 5 percent of traffic consisted of cars. (source Feddes en de Lange, p.12)

Film of Amsterdam in 1920 made by riders organisation ANWB.

Planning for cyclists, and for cars

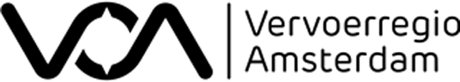

The fact that cycling is important in Amsterdam is reflected in policy. The new neighbourhoods planned in the Amsterdam Expansion Plan (Algemeen Uitbreidings Plan, AUP, 1935) are within cycling distance of the Centre. This map shows that the new expansions are all within 30 minutes by bike from the city centre. Amsterdam thus remains a cycling city.

New neighborhoods within 30 minutes cycling from the city center. From: Algemeen Uitbreidings Plan, municipality of Amsterdam 1935

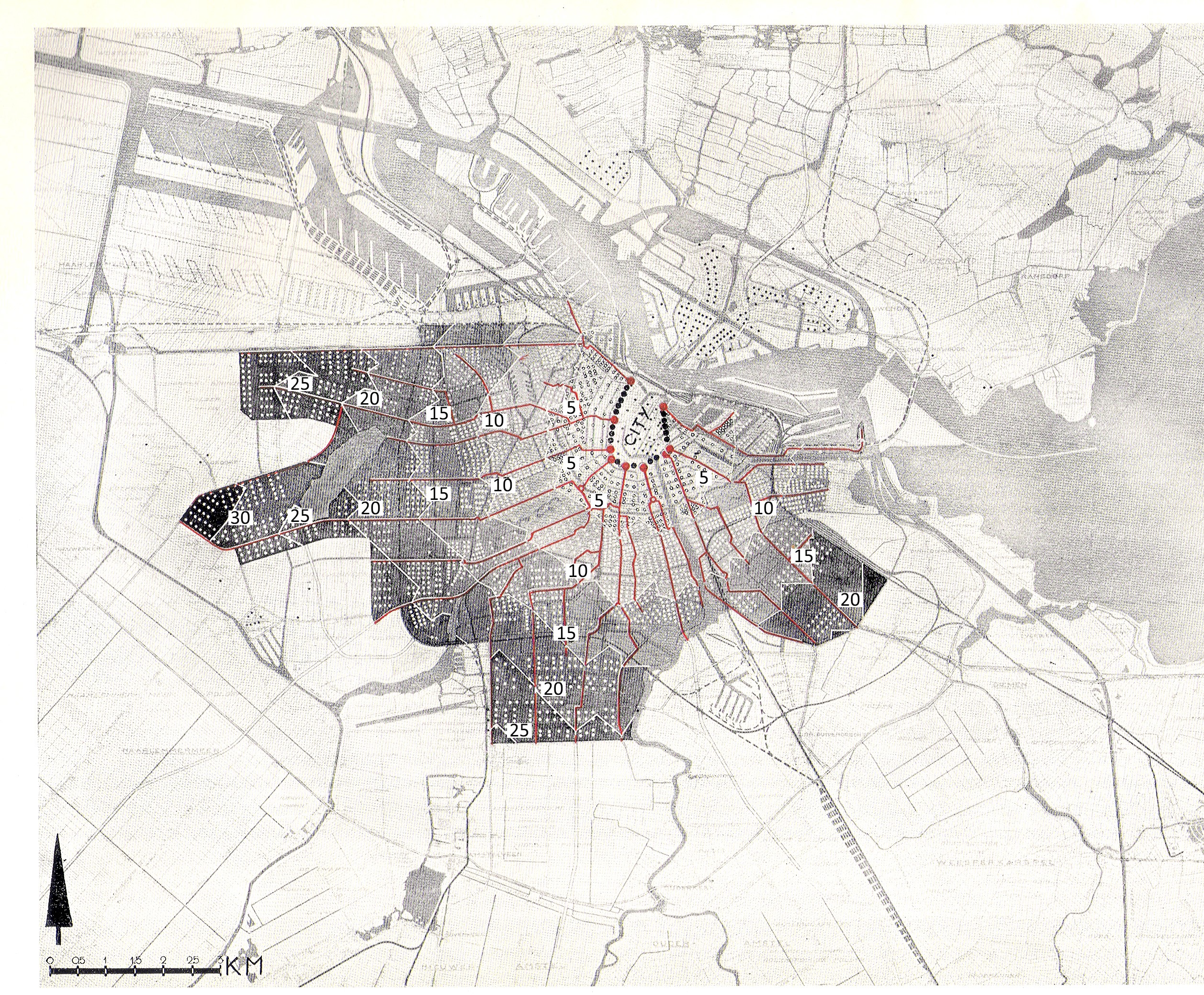

But the AUP plans for the car as well, the emerging vehicle. With streets in the existing city often too narrow for the growing number of cars, the roads in the new districts are given plenty of width. And separate cycle paths are being built along these wide main roads. These are the first planned cycle paths in Amsterdam!

Planed layout for Röellstraat, main road in Nieuw West. From: Algemeen Uitbreidings Plan, gemeente Amsterdam, 1935

More and more cars

After WW2 and the lean 1950s, the volume of cars started to grow considerably. The government welcomes the ‘general motorisation’. The national ‘policy of overflow’ makes that Amsterdammers move to new housing estates in ‘grow municipalities’ at a driving distance from the city. There is space for a house with a garden and a car in front of the door. The result is that the places where people live and work get further apart.

The city council of Amsterdam focuses its traffic policy entirely on the car as well. Partly due to the growing flow of commuters by car. Policymakers and traffic experts see cycling as a dying business. They ignore the bicycle in their plans. The vision for the future is a large-scale, modern city in which places for homes and work are connected by motorways. For example, the tunnel under river IJ (1968) is built for motorised traffic only.

Lots of space for cars on widened-up Weesperstraat (1977). Photo: Stadsarchief Amsterdam, DRO

One vote difference

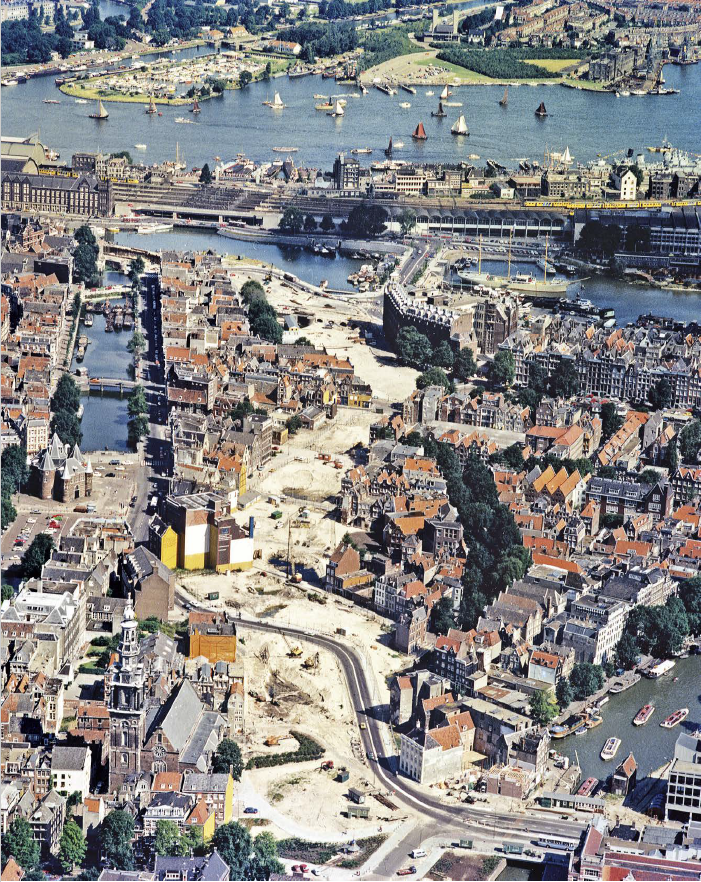

But from the 1960’s things slowly start changing. Amsterdammers see their city getting overwhelmed and damaged by so many cars. Resistance is emerging. The battle is focused on a plan to build a metro line through Nieuwmarkt area, with on top of it a four-lane road from Weesperstraat to Central Station. Thanks to a remarkable coalition of squatters, heritage conservationists and concerned citizens, opinions are changing. Ultimately, 21 council members vote in favour and 22 against the four-lane road. With only one vote difference the plan for the four-lane street was rejected, and spatial policy started to change!

The result can be seen on the bridge that connects Jodenbreestraat with Sint Antoniesbreestraat: Jodenbreestraat had already been broadened, Sint Antoniesbreestraat retained its historical width. On the bridge, a monument with a turtle commemorates this turnaround.

Nieuwmarkt area around 1975, demolition for building the metro, and the four-lane road that wasn’t built. Photo: Gerhard Jaeger

114 traffic fatalities

Once it was clear that the car was not the way forward for the city, the bicycle came back into the picture. But cycling was a dangerous activity back then. The number of traffic accidents increased enormously, reaching a low point: 114 deaths in the city in 1970. Many of them cyclists. In recent years, this number is between 15 and 20. An influential pressure group in the 1970s was ‘Stop de Kindermoord’ (Stop the Child murder). They protested against the horrific lack of traffic safety and against the apathy and fatalism about it of the authorities and the population. This initiative received great support in Amsterdam as well. ‘The contempt for death that Amsterdam cyclists need to display is admirable, but should be unnecessary’, PvdA (the labour party) wrote in its election manifesto for the 1974 municipal elections.

Kinkerstraat full of cars, 1984. Photo: Stadsarchief Amsterdam, DRO

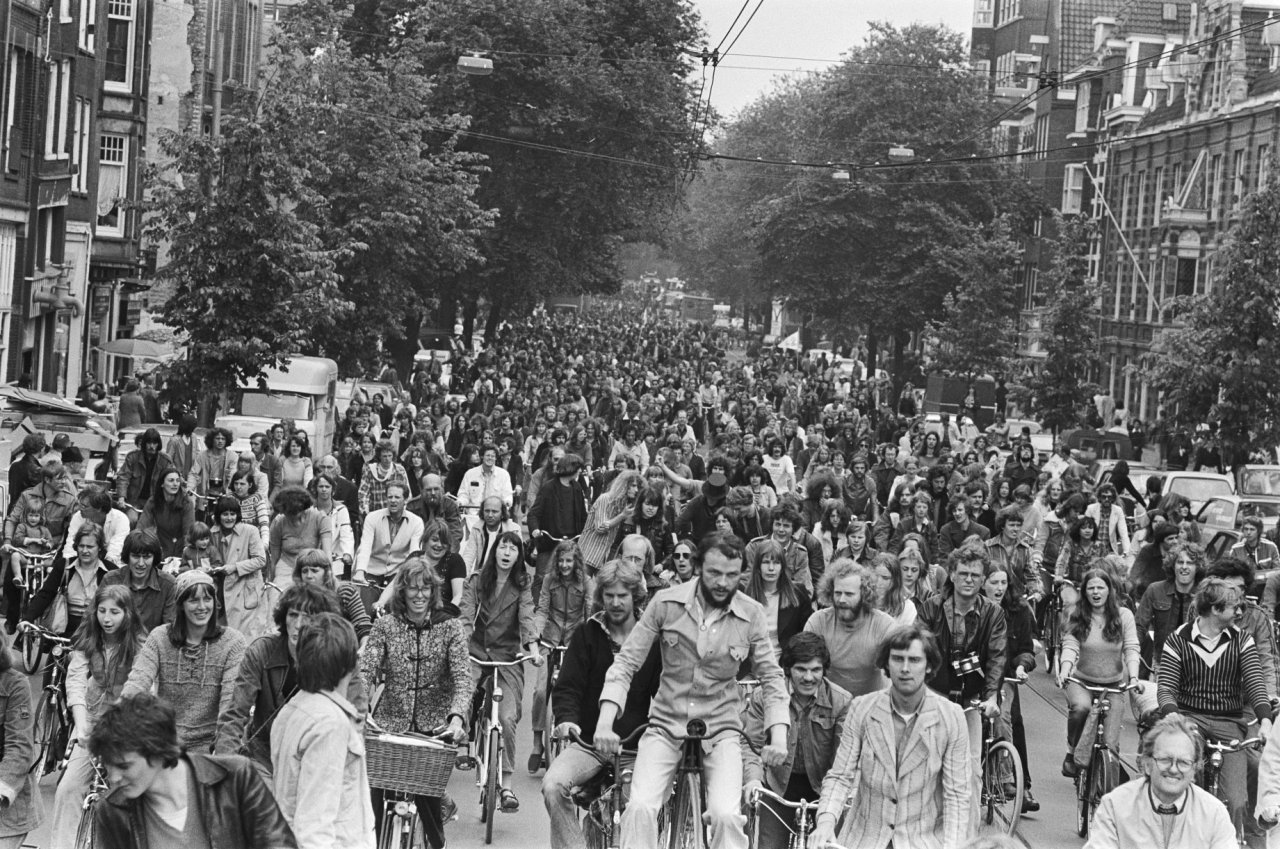

Massive bicycle demonstrations

It is hard to imagine how dominant the car was at that time. Cyclists even avoided some streets because they were simply impossible to get through.

In the 1970s, a coalition of concerned citizens, cyclists, environmentalists and other activists organised large bicycle demonstrations: Amsterdam Fietst! These were not only about cycling and traffic safety, but also about environmental issues and the quality of life in the city.

In 1975, the bicycle got its own advocate: the Fietsersbond, Cyclists’ Union. And an Amsterdam branch a year later.

Bicycle demonstration in 1977. Photo: Rob Boogaerts

Compact city

Decisive for the future of traffic in Amsterdam was the new vision for the city. Amsterdam will become a ‘compact city’ and not an expanding city connected by major roads. Amsterdam will remain ‘compact’, on cycling scale and with the bicycle as the ideal means of transport. Under the leadership of alderman Michael van der Vlis, bicycle policy started. Car traffic is restricted with a stricter parking policy, speed bumps, one-way traffic etc.

From the 1980’s these sort of blocks and curbes are planted to prevent ‘wrong parking’ on sidewalks etc. From: Handboek Fiets Amsterdam, Gemeente Amsterdam and Fietsersbond Amsterdam, 1991

A main network for cyclists

A major goal of the cycling policy that is implemented since 1978 is to make cycling safe and enjoyable (again). Amsterdam is going to work on a ‘Main Network for Cyclists’, a network of safe routes for cyclists. This is done with thousands of small and large measures, with vision, courage and perseverance, and over the years with increasing expertise.

Measures such as two-way traffic for cyclists in streets where cars have one-way traffic, speed bumps, safe intersections and crossings, making (parts of) streets car-quiet or car-free, bridges for cyclists etc.

Individually, these may not be spectacular measures, but together they lead to a city where cycling is good in (almost) every street. The most difficult streets are the main roads where all the hustle and bustle come together: pedestrians, cyclists, cars, trams, shops, destinations etc. With great effort, also these streets get more space for cyclists and less for cars. Street by street, over a period of decades.

Segrageted cycle paths on Ceintuurbaan, built ca 2007. Photo: Municipality of Amsterdam

Advocate for cyclists

The Amsterdam Cyclists’ Union, is the representative of the interests of cyclists. They become an important driving force and advisor to the municipality in making Amsterdam better for cycling. This approach is bearing fruit. In 1996, car use in older city districts decreased for the first time and bicycle use increased. (source Policy Evaluation Traffic and Transport 1996). Traffic safety in the city also improved.

The knowledge gained from working on the bike city is recorded in the Handbook Fiets Amsterdam. This world-first manual for bicycle-inclusive design is a joint product of the Cyclists’ Union and the municipality.

Bike congestion

In the 21st century, cycling continues to grow. The cycle paths, together with all other measures, prove successful. So successful, that it overwhelms some of the cycle paths. They have become too narrow. The term bike congestion appears. The diversity on the cycle paths increases as well: Around 2004, more and more moped riders appear on the cycle paths, causing inconvenience and danger. Countermeasures follow: From 2019, moped riders must ride on the roadway and wear a helmet in Amsterdam within the A10 ring road. That makes it quieter and safer on the cycle paths.

Morning rush hour on Amstelveenseweg. Photo: ML de Lange

But before long there is again something new, more and more e-bikes. In all kinds of guises: fast cyclists on e-bikes, delivery services with large delivery e-bikes, parents with children in cargo e-bikes, fat-tyre bikes. An interesting option for traveling longer distances (the residents in the region) or taking cargo, but also a new challenge: How is safety ensured with more and more fast cyclists, and how can cycling remain pleasant for vulnerable cyclists (elderly, children, less skilled cyclists)?

Never finished

Nowadays, Amsterdam is considered one of the best bike cities in the world. There is a balance between cars and bicycles, and cycling is a good option. But it isn’t perfect, obviously. There will always be (new) challenges. Such as the current bike crowding, (too) fast e-bikes, dangerous behaviour and growing numbers of vulnerable cyclists such as the elderly.

The municipality continues working on the bike city. Together with cyclists. The introduction of a maximum speed of 30 km/h in the city can help make cycling safer. And various options are investigated to bring back space and quietness on the cycle path. One of those is to introduce a maximum (advisory) speed on the cycle path and let fast cyclists ride on the roadway.

Bike city Amsterdam is evolving constantly.